Saturn's biggest moon, Titan, is a world both acquainted and alien,, and the mysteries just

preserve getting higher.

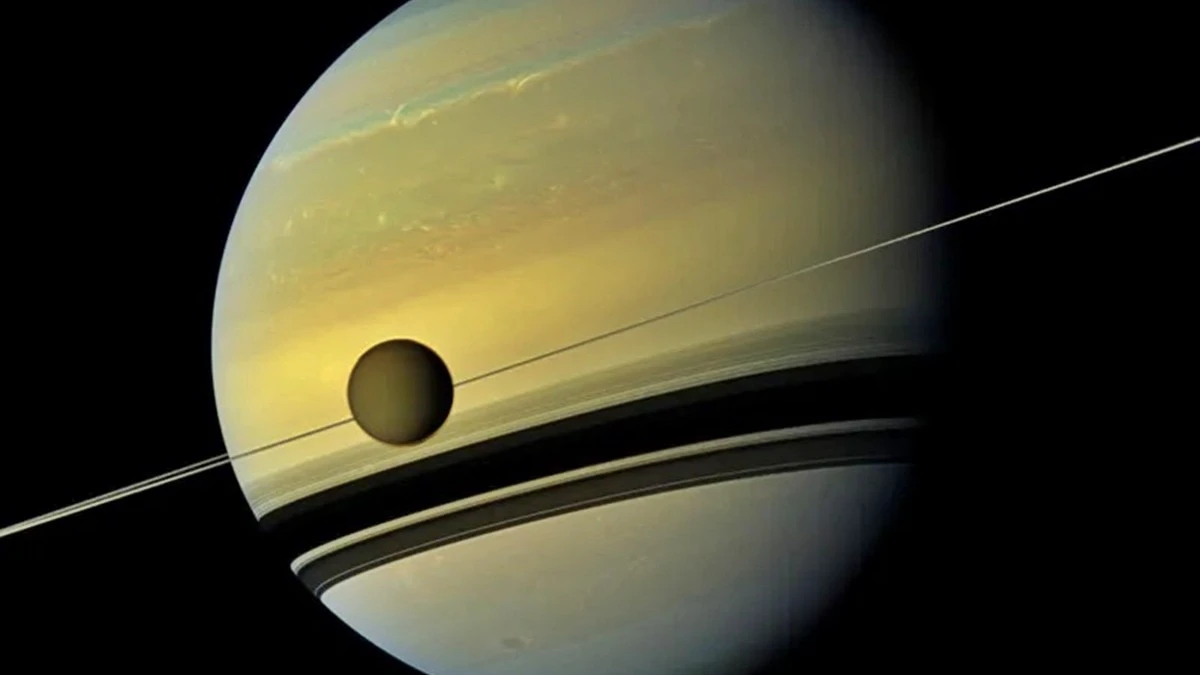

Cloaked in a thick, yellowish haze, Titan is the handiest place in our solar system besides Earth where rain falls from the sky and fills lakes and rivers.

However, on Titan, the rain is not water—it is liquid methane and ethane, hydrocarbons that might be gases in the world but behave as cold liquids in Titan's frigid surroundings.

Latest observations by NASA's james Webb Space Telescope, together with images from the Keck II telescope, have supplied the first proof of cloud convection in Titan's northern hemisphere, over a place dotted with lakes and seas.

Those photos of Titan had been taken by means of NASA's james Webb Space Telescope on July 11, 2023 (top row), and the groundbased W.M. Keck Observatories on July 14, 2023. (Photo: NASA)

These clouds, made of methane, form similarly to water clouds on this planet: methane evaporates from Titan's surface, rises, cools, and condenses into clouds, which sometimes unleash oily methane rain onto the icy floor.

This methane rain feeds Titan's lakes and rivers, typically located close to its North Pole, where the landscape is fashioned with the aid of cycles of evaporation and rainfall.

Titan's weather is driven by a methane cycle that mirrors Earth's water cycle. Methane clouds form, rain falls, and the liquid gathers in

lakes and seas earlier than evaporating again.

In contrast to Earth, wherein water is the important aspect for life and climate, Titan's environment and surface are ruled by methane and ethane. The surface temperature is a bone-chilling -179°C, so water is frozen as hard as rock, while methane flows freely.

Scientists are fascinated by Titan's complex chemistry.

Webb's latest observations even detected a molecule known as the methyl radical (CH), offering a glimpse into the ongoing chemical reactions in Titan's environment.

The chemical substances behave as chilly liquids in Titan's frigid environment. (Picture: NASA)

Those reactions, driven by means of sunlight and Saturn's magnetic subject, ruin aside methane and build extra complex organic molecules—a number of the constructing blocks of life.

Titan's methane is slowly misplaced to space, so scientists agree that there ought to be underground reservoirs or procedures that fill it up, keeping the rain and lakes going.

If that supply ever runs out,

Titan may want to emerge as a dry, dusty international.

For now, Titan remains a place in which it sincerely rains from hydrocarbon clouds—reminding us that weather, within the universe, can take many unusual and fantastic forms.

click and follow Indiaherald WhatsApp channel

click and follow Indiaherald WhatsApp channel