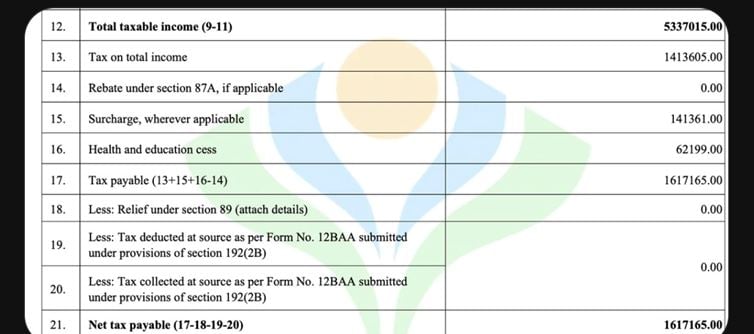

The tweet begins with a personal lament: "I could have made a road outside of my home with that kind of tax. I feel sad and feel like crying at the same time." This statement reflects a deep sense of disillusionment, suggesting that the taxpayer believes their financial burden could have been better utilized for local infrastructure rather than being absorbed into an inefficient system. The accompanying image of a tax document, likely from the Income Tax Return (ITR) form, provides a concrete basis for this frustration, detailing a tax liability of ₹1,61,71,65.00 for the assessment year.

The tax breakdown reveals a taxable income of ₹5,33,70,15.00, with a tax on total income amounting to ₹1,41,36,05.00. Additional charges include a surcharge of ₹14,13,61.00 and a health and education cess of ₹6,21,99.00, bringing the total tax payable to ₹1,61,71,65.00 after accounting for no relief or provisions. The taxpayer highlights the health and education cess—₹6,21,99.00—as particularly galling, noting it exceeds their insurance premium and questioning its purpose given the lack of visible improvements in healthcare or education. They also mention paying ₹5 lakh (5L) in car purchase tax and an estimated ₹1-2 lakh in other indirect taxes, underscoring the cumulative financial strain.

The tax breakdown reveals a taxable income of ₹5,33,70,15.00, with a tax on total income amounting to ₹1,41,36,05.00. Additional charges include a surcharge of ₹14,13,61.00 and a health and education cess of ₹6,21,99.00, bringing the total tax payable to ₹1,61,71,65.00 after accounting for no relief or provisions. The taxpayer highlights the health and education cess—₹6,21,99.00—as particularly galling, noting it exceeds their insurance premium and questioning its purpose given the lack of visible improvements in healthcare or education. They also mention paying ₹5 lakh (5L) in car purchase tax and an estimated ₹1-2 lakh in other indirect taxes, underscoring the cumulative financial strain.The post taps into a wider narrative of taxpayer frustration in India, where individuals often feel that their contributions—through income tax, goods and services tax (GST), and various cesses—are not reflected in the quality of public services. The health and education cess, levied at 4% on tax payable, is intended to fund improvements in these sectors, particularly in rural and underserved areas. However, the taxpayer’s experience of poor infrastructure, such as an unmaintained road, suggests a disconnect between policy intent and execution. Indirect taxes, including those on car purchases, further compound the burden, with the automotive sector facing a 28% GST rate plus additional cess, as noted in related web discussions.

The taxpayer’s cry reflects a broader challenge in India’s taxation and infrastructure development system. Despite significant tax collections—projected to fund national highways and public services—the Comptroller and Auditor General has noted procedural inefficiencies and inadequate resources, such as insufficient ambulances and patrol vehicles on national highways. The post suggests a need for reforms, such as simplifying tax structures, ensuring targeted spending on infrastructure, and enhancing local governance to address community-specific needs like roads. It also raises questions about the effectiveness of cesses and the equitable distribution of public funds.

click and follow Indiaherald WhatsApp channel

click and follow Indiaherald WhatsApp channel